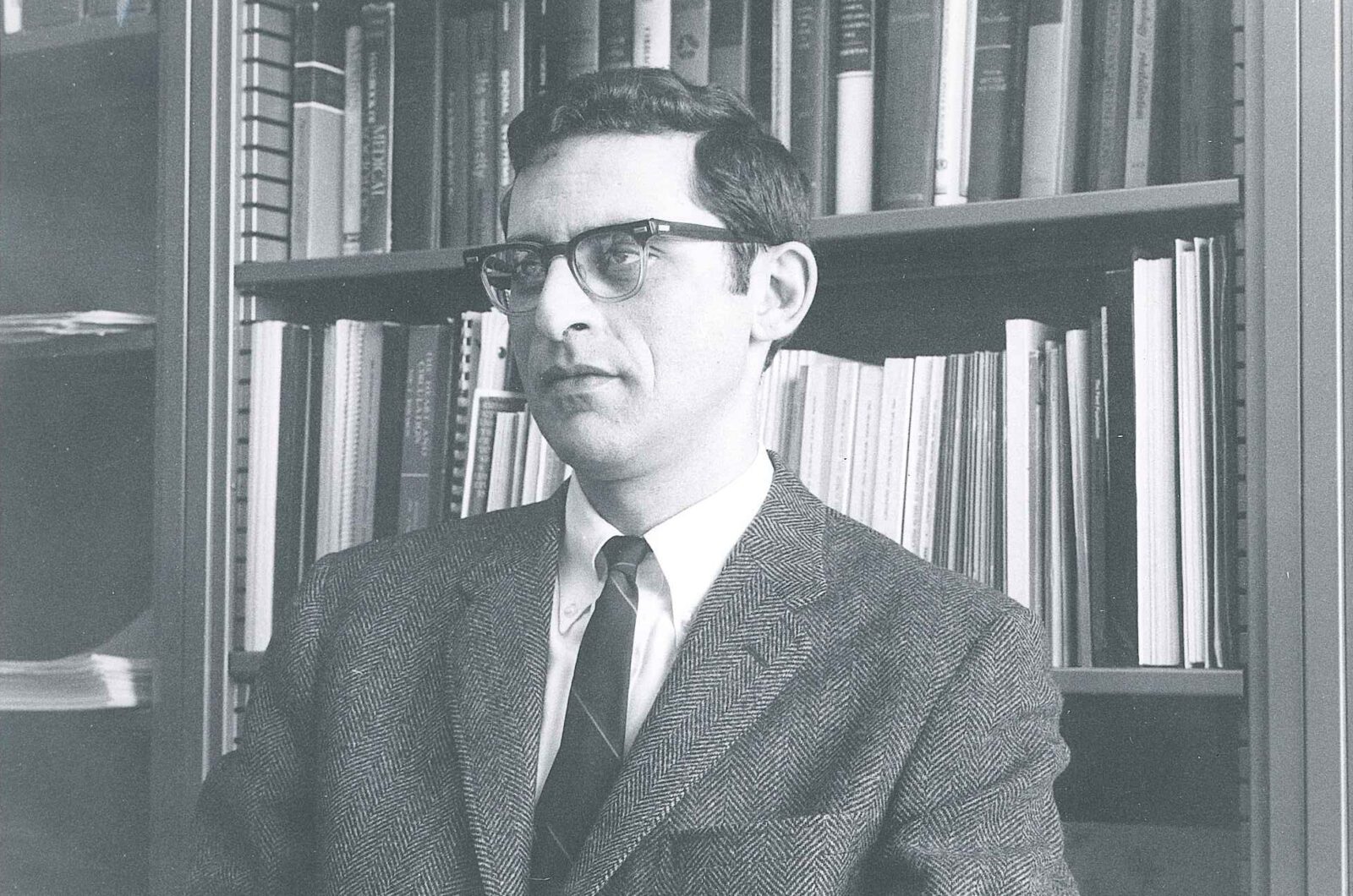

S. Leonard Syme: The father of social epidemiology

Second in a series on outstanding emeritus faculty at Berkeley Public Health

- By Sheila Kaplan

- 11 min. read ▪ Published

Recently, S. Leonard Syme, professor emeritus at Berkeley Public Health, wondered why Daniel, the kind and capable young waiter at his local cafe, wasn’t in college.

“One day I asked him who he was and what was going on with him,” Syme recalled. “It turned out he was a young man in trouble.”

Syme, then 90 and retired for 22 years, could not resist helping one more person find his path.

“As we talked over time, I could tell that he really was special,” Syme said. “Eventually we decided that going to college was a good thing to do – but his grades were dreadful. We decided on a small college in Northern Colorado. I wrote him a letter of recommendation like I had never done before, and they accepted him.”

That story doesn’t surprise Lisa Berkman, an internationally recognized social epidemiologist, now at Harvard University, who studied with Syme in the 1970s.

“Len has an incredibly good sense for picking people who are intellectually courageous—for seeing the future for people,” she said. “It’s why he could tell a waiter to go to college. It’s almost like Len just saw your brains and your creativity. He didn’t see your outside, he saw your inside.”

Syme’s impact as a scholar is well known. As a professor of epidemiology and community health—and prior to that, working for the National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies—he demonstrated the impact that such factors as poverty, stress, social class, and social isolation have on health. His research examined these psycho-social stressors on people around the world: bus drivers in San Francisco, civil servants in London, and Japanese men at home and abroad.

He served for more than 20 years as co-principal investigator at Berkeley Public Health’s Health Research for Action, where his team developed community interventions to prevent disease and promote health.

One project was the publication of a parents guide to raising healthy children, from birth to age five. More than three million copies, in five languages, have been distributed to new parents in California.

Another program, sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency, was aimed at showing people in vulnerable populations – including people with asthma, tribal natives, older Hmong adults, farmworkers and the deaf – how to protect themselves from wildfire smoke.

Along the way, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences and won many coveted awards for research and teaching, among them the Wade Hampton Frost Leadership Award—one of the most prestigious awards in the field of epidemiology—from the American Public Health Association for developing the study of social epidemiology. He also received the Berkeley Citation for distinguished service to the university and was given the Panunzio Prize as Outstanding Emeritus Professor in the statewide university system.

Syme’s drive to examine the psycho-social factors that compromise one’s ability to stay healthy—rather than following the traditional medical model to study the etiology of individual diseases—has become such a pillar of public health thinking that it’s hard to remember that it was, during the 1960s and much of the 1970s, heresy.

“It was the fringe of the fringe,” said Sir Michael Marmot, director of the Institute of Health Equity at University College London, who came to Berkeley to study with Syme in the mid-1970s. “Epidemiology was the fringe part of medicine, and social epidemiology was the fringe part of epidemiology.”

“Len made respectable the idea that social and psychosocial influences on disease, cardiovascular disease in particular, could be important,” Marmot said. “It wasn’t just, ‘We have these fuzzy ideas of how social factors impact on health.’ It was with scientific rigor, which made it respectable.”

Berkman, now director of Harvard’s Center for Population and Development Studies, called Syme the leading mentor of a generation of social epidemiologists.

“At the time I started graduate school at Berkeley, there were maybe two or three people in the world who were doing this,” she said, “and Len was the person who trained the most people and was very pathbreaking.

“My work on inequality is fundamentally based on his thinking. I now have, in a generational sense, his grandchildren. The people I trained are now running research units and have their own doctoral students.”

A tough childhood led to a life of empathy

It has been an unusual journey for a boy who spent an uneasy childhood in Winnipeg, Canada, then a small, dreary city in the Canadian prairie. In his 2011 autobiography, Memoir of a Useless Boy, Syme describes surviving tough threats from inside and outside his home which provided challenges but also gave him empathy for people facing hard obstacles and a conviction of the protective powers of strong social ties and, above all, hope.

His book recounts his experience as a Jewish boy in Winnipeg, a majority Ukrainian city in the 1930s and ’40s, where he often hid from “Ukrainian kids hunting down the Jewish kids as if they were conducting a pogrom back in the old country.” Syme also chronicles routine abuse from his father, who often belittled him as “useless.” It was a painful relationship that spurred his determination to prove his father wrong.

Syme was the first in his family to attend college, starting at a local school and then transferring to the University of Manitoba in 1949. The school was very small but nearly the entire faculty were Oxford or Cambridge-trained teachers, working in the Canadian prairie until the post-war job market opened up back home. He ultimately received his bachelors and masters degrees from UCLA in 1955 and then landed at Yale, where he pursued a PhD in what was then called the sociology of medicine. He avoided the Korean War by getting a military deferment to work with the U.S. Public Health Service, then landed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Syme’s early research at NIH, examining the psychosocial causes of heart disease, was scoffed at by the established medical community. When he presented his theory on the influence of social factors on health to an American Heart Association meeting in Miami, Syme was chastised.

“One man took me aside and said, ‘Don’t ever do that again,” he recalled. “He told me to stick with the things we already know about: high-serum cholesterol, cigarette smoking, high blood pressure.”

But he already knew that he wanted to answer the questions, Why do people in high social classes enjoy better health than poor people do? Is it genetics? Better medical care? What, exactly, is at work here?

“Everyone in public health knows that this is the major question,” he said.

In 1968, Symes landed at Berkeley to continue his controversial line of inquiry.

A major breakthrough, Syme said, came not from himself but from his former graduate student Sir Michael Marmot, who in 1991, while studying the health of 10,000 British civil servants, discovered there was a gradient by social class ranking. Syme said that he then revisited his own research and saw similar findings.

The factor that made the difference, according to Syme, was what he calls “control of destiny,” the ability of people to deal with the issues that confront them in their daily lives.

“Less control affects immune functioning in the body,” he said. “Social forces have been shown to affect immune functioning. They can actually change bodily function and we can measure it.”

He’s pleased to see the field of social epidemiology explode, and remains, he said, “in awe of many of his former students,” whom he said have advanced the field far beyond his own contributions.

Linda Neuhauser, clinical professor of community health sciences at Berkeley Public Health and co-principal investigator at the Health Research for Action Center, met Syme when she was a doctoral student.

“He’s brilliant, obviously, and highly innovative,” she said. “To come up with something that now is the foundation of public health. It’s not everyday you have that.”

Neuhauser praised Syme’s work as a mentor, and noted that he’s long made a point of helping women, people of color, and people who were the first in their family to go to college.

“He’d seek those people out,” Neuhauser said. “He’d say, ‘See so and so, I’m going to mentor her and she’s going to be somebody big—more important than me!’ He’d look for opportunities, get them on grants and scholarships.”

In the early 2000s, Neuhauser worked with Syme to create what they called “public health interventions,” a move from pure research to a more activist approach, which they taught together.

“In many areas we already know what would make people healthier, we just weren’t doing anything about it,” she said, “So we began to discuss how to do it, and how to teach public health intervention, to link research with action using participatory methods and social determinants in health.”

“Len is very provocative. He’s not afraid to challenge somebody and say, ‘Come on, this isn’t working, why are you doing it?”’

Almost a century of thinking outside the box

These days, at age 91, Syme spends much of his time with family and friends, and his legion of former students; but he is still working to promote health equity.

Most recently, he has joined forces with David Erickson, a senior vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, whom he helped inspire to use the bank’s clout to improve education for children.

“The Federal Reserve Bank focuses on the economy, on productivity, on joblessness, etc.,” Syme said. “In our talks, the importance of children was introduced, and he jumped on the idea and wrote a whole book about that.”

“Instead of focusing only on housing and jobs, which are really important, he wants to give children a high quality education. It’s a big deal. The key issue is that if you leave the children behind, you’ve accomplished little.’’

And what became of Daniel the waiter? He writes to Syme often and visits whenever he’s home from college…where he gets straight As.